X c = M y m = ∬ R x d A ∬ R d A and y c = M x m = ∬ R y d A ∬ R d A, x c = M y m = ∬ R x d A ∬ R d A = ∫ x = 1 x = 3 ∫ y = 0 y = e x x d y d x ∫ x = 1 x = 3 ∫ y = 0 y = e x d y d x = ∫ x = 1 x = 3 x e x d x ∫ x = 1 x = 3 e x d x = 2 e 3 e 3 − e = 2 e 2 e 2 − 1, y c = M x m = ∬ R y d A ∬ R d A = ∫ x = 1 x = 3 ∫ y = 0 y = e x y d y d x ∫ x = 1 x = 3 ∫ y = 0 y = e x d y d x = ∫ x = 1 x = 3 e 2 x 2 d x ∫ x = 1 x = 3 e x d x = 1 4 e 2 ( e 4 − 1 ) e ( e 2 − 1 ) = 1 4 e ( e 2 + 1 ). The lamina is perfectly balanced about its center of mass. Figure 5.64 shows a point P P as the center of mass of a lamina.

If the object has uniform density, the center of mass is the geometric center of the object, which is called the centroid. The center of mass is also known as the center of gravity if the object is in a uniform gravitational field. The density is usually considered to be a constant number when the lamina or the object is homogeneous that is, the object has uniform density. In this section we develop computational techniques for finding the center of mass and moments of inertia of several types of physical objects, using double integrals for a lamina (flat plate) and triple integrals for a three-dimensional object with variable density. We have already discussed a few applications of multiple integrals, such as finding areas, volumes, and the average value of a function over a bounded region.

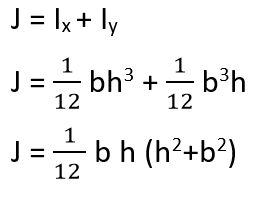

5.6.2 Use double integrals to find the moment of inertia of a two-dimensional object.5.6.1 Use double integrals to locate the center of mass of a two-dimensional object.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)